May 1, 2014; The Guardian

At a recent program of Georgetown Law School and Independent Sector on the for-profit social enterprise dynamic in the U.S., the gap between the hype and the reality of social impact bonds was evident. A presenter from Social Finance acknowledged that for all of the years of hype, there are only four Social Impact Bond projects actually operating in the U.S. There may be more in the works, but the breathless endorsement of the concept in the U.S. relies on an exceptionally thin repertoire of SIB experience—of which not one has reached even an interim payment point.

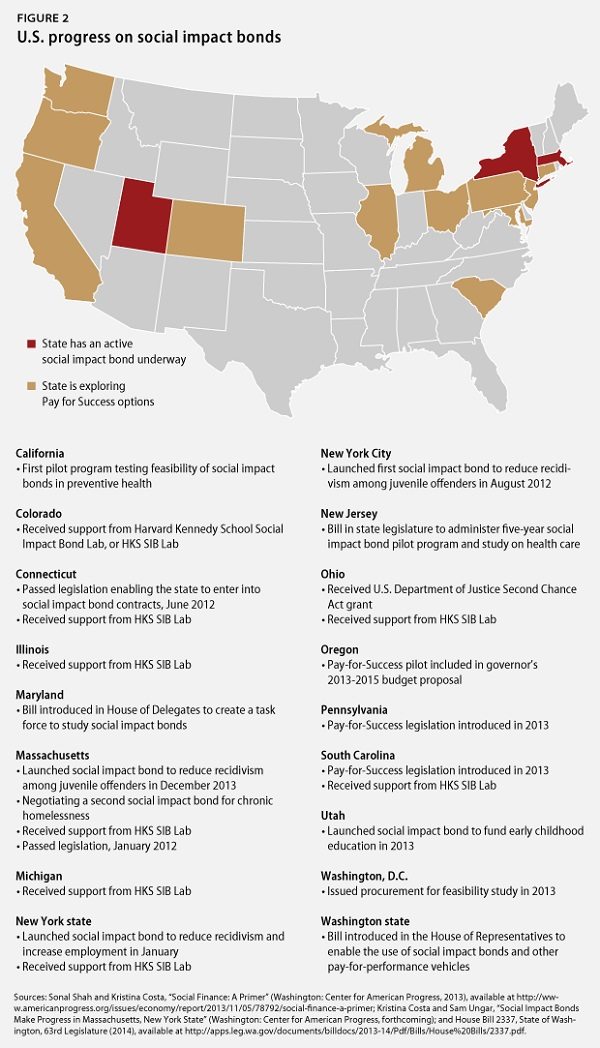

That contrasts somewhat with the constant drumbeat of promotional articles, white papers, and reports on the upside of social impact bonds, which have been endorsed by a number of states and by the Obama administration (as “pay for success,” since, strictly speaking, social impact bonds aren’t really bonds at all). The Center for American Progress identifies 15 states with social impact bond projects either underway (New York, Utah, and Massachusetts) or under consideration (Washington state, the District of Columbia, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Maryland, Illinois, Connecticut, Ohio, New Jersey, California, and Colorado):

The concrete experience that advocates in the U.S. have drawn on to justify their SIB enthusiasm is from the UK, which saw a number of SIBs get underway with the active involvement and promotion of the Tory/Liberal government of David Cameron. The Cameron government even has a specific office dedicated to promoting SIBs. The first SIB in the world appears to have been in the UK, a project to reduce recidivism, much like the dominant program focus of the U.S. social impact bonds in Massachusetts and New York.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This past week, SIB enthusiasts encountered some reason for nervousness. The Guardian published an article titled “Social Impact Bonds: Is the Dream Over?,” following up on the news that the UK government’s first SIB, the recidivism project at the prison in Peterborough, would be replaced by an “alternative arrangement.” The government has revealed a new policy initiative called Transforming Rehabilitation, whose structure doesn’t fit the SIB as currently structured. Both the government and the SIB sponsors at Social Finance took pains to explain that the new policy doesn’t mean that the Peterborough SIB was a failure, but had been operating as expected, despite its not having reached its first assessment and payment point.

Fundamentally, the one-site experiment at HM Prison Peterborough could be replaced by simply having the government fund what works on a broader, national scale. If government money is the take-out, and if the program being tested, structured based on past knowledge and experience, is known to work reasonably well, there seems to be little justification for withholding the “treatment” from a broader population of potential beneficiaries.

Commenting to the Guardian, Charlotte Ravenscroft of the National Council of Voluntary Organisations observed, “One immediate lesson is that a Sib may be sensitive to policy shifts. Regardless of whether the policy change itself is positive, this sort of uncertainty could limit the appetite of potential Sib investors.” In other words, if government has the funding and knows what policy should be pursued, policy change might be the preferred avenue of social change over limited, investor-oriented SIBs. As consultant Abigail Rotheroe wrote for the Guardian, “although the Peterborough Sib was meeting targets and getting better over time, the broader policy imperative to improve outcomes for offenders rightly took precedence.”

That is as it should be. It seems that the promoters of SIBs are so taken with the SIB form and structure that they may be overlooking the more valuable route for social change: enacting and implementing public policies that address the issue more comprehensively, rather than waiting for limited SIB experiments where the focus drifts inordinately to the attractiveness to investors (and the consultants that make money from promoting and structuring SIBs).

Don’t worry. The Cameron government is hardly abandoning the SIB model. Although policy change has made the Peterborough SIB a little passé, the government immediately announced a £30m social impact bond effort focused on developing innovative approaches to education and employment challenges for as many as 20,000 young people between the ages of 14 and 24. It is also entirely possible that the new Transforming Rehabilitation program will end up with a means of incorporating the Peterborough SIB effort to date to ensure some sort of payment on the bond.

The enthusiasm may be waning on this side of the Atlantic, too. At a congressional hearing on social impact bonds, Senator Mark Warner (D-VA), chair of the Senate Budget Committee’s Government Performance Task Force, gave SIBs a lukewarm endorsement as potentially having “some value.” That was in contrast to the commentary of Maine senator Angus King, an Independent who generally caucuses with the Democrats. “I have a radical idea,” said King. “Instead of trying to contract out with social impact bonds, why doesn’t the government just get it right?” That seems to be a logical alternative to finding ways of providing profit margins to private investors for doing what most people already know should be done.—Rick Cohen