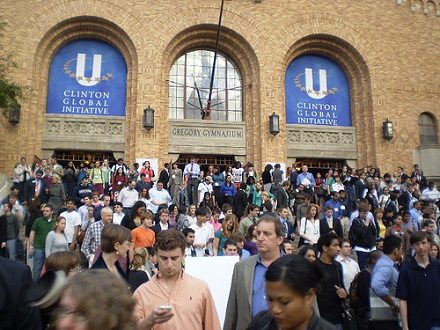

September 25, 2012; Source: TIME

Stories from the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) are getting great circulation in corporate social responsibility circles, including the recently concluded Social Capital Markets (SOCAP) conference in San Francisco. President Clinton’s philanthropic initiatives have embraced markets and businesses and, consequently, the people who were given the dais at the CGI conference get an added measure of notice and respect in mainstream circles. Social capitalists imagine a corporate world where the return motivations of capitalists change through experience, education, self-regulation, and a different mix of motivations and incentives that would make them more socially responsible.

Scott Medintz covered the CGI panel discussion that examined how to deal with the fact that “the profit motive is sometimes at odds with the broader interests of society at large.” Such language underemphasizes that many of the world’s problems—try the recent economic crisis—were created by profit-seeking, profit-maximizing entities. “Can Companies Be Good and Do Well?” Medintz’s headline asks. It’s not a new question but the answer—that “private enterprises…must be parts of the solutions” to social and economic problems—has, according to Medintz, garnered agreement to the extent of “something approaching unanimity.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Panelist Lynn Stout, a Cornell Law School professor, said that there is no reason to run corporations simply to maximize stock prices and shareholder value and, in fact, “we all know it’s not working out well.” Panelist Jochen Zeitz, chairman of German sneaker company PUMA and the chief sustainability officer for its parent company, argued that instead of traditional financial metrics, corporations should be evaluated against, as Medintz puts it, a “more holistic set of measurements…[called] an Environmental Profit & Loss Account, which takes into account a company’s environmental impact up and down the supply chain.” Panelist Arif Naqvi, CEO of the Dubai-based Abraaj Holding, agreed that, in Medintz’s words, “long-term sustainability and long-term profitability go hand-in-hand.”

If such positions are approaching unanimous acceptance, as the author writes, then the corporate world must simply be getting its act together a bit slowly, since there isn’t widespread evidence that social responsibility has taken hold among corporations. But we don’t buy the idea that such a consensus exists. Maybe that’s because many corporate executives in the U.S. favor reducing their taxes while compelling working class and middle class taxpayers to ante up, often at effective tax rates much higher than what some millionaires and even billionaires might pay. Or maybe it’s the resistance of too many banks to the Consumer Financial Protection Board provisions of the Dodd-Frank legislation, which is meant to help recipients of loans and mortgages be better protected, more educated, and hopefully more sustainable consumers.

It’s great to see an emerging class of responsible corporate leaders in some corporations, but for others, social responsibility is more branding and marketing than substance. To get corporations to look beyond profits and do the right thing, it may take the unbelievable persuasiveness of a Bill Clinton, but it also probably requires continued government monitoring and oversight—and regulation and perhaps taxation.

On the panel, Stout came out in favor of a stock transfer tax, which we have written about many times (for example, see here and here). Bill Gates has endorsed the idea, but the number of other corporate leaders joining him is few, and U.S. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner quickly knocked the idea down. Social responsibility language, promotion, and branding are all fine, but responsible corporations have to be socially responsible in many ways; that includes their relations with labor and government. We suspect they have some big stretches of ground to cover before getting there.—Rick Cohen