Editors’ note: The Management Assistance Group (MAG) strengthens visionary social justice organizations, leaders, and networks to create a more just world. To those ends, MAG develops innovative approaches to capacity building; conducts research on critical organizational issues faced by clients; and shares insights with the social justice sector and the nonprofit organizational development field.

Two years ago, President Barack Obama announced a regulatory change that guarantees labor protections for an overlooked group of workers: home caregivers. At his side, beaming with triumph, were members of the Caring Across Generations campaign.

Caring Across Generations (CAG) is a diverse coalition that includes caregivers, senior citizens, people with disabilities, and immigrant advocacy organizations. The group came together to address interconnected crises: a shortage of home caregivers to support the growing numbers of elderly and disabled Americans; a lack of basic job protections—such as minimum wage and overtime laws—for those caregivers; and the lack of affordable long-term care services for individuals and families.

This unlikely alliance has borne fruit. In addition to winning its short-term regulatory goal, CAG is addressing longer-term, structural problems. It has made visible the plight of workers in the “informal” sector, and it has united groups thathave sometimes been at odds to understand and act upon their common interests.

Importantly, CAG demonstrates the power and promise of networked approaches to social change. Cross-issue “movement networks,” in particular, can create a force larger than the sum of their parts. They can deploy a diverse array of assets and strategies, enabling advocates to amass political power, scale up impact, and win—both in the policy arena and in the battle for hearts and minds.1

Yet while movement networks offer extraordinary leverage, they also present outsized challenges. With fluid boundaries of structure and membership, movement networks (and the organizations that comprise them) require new approaches to management and leadership—approaches that are different from those employed by traditional nonprofit organizations and short-term, issue-based coalitions.

Like the social issues they address, movement networks are complex. They must balance the autonomy of individual members with the need for collective action and accountability. They must address the needs of both existing and emerging members while straddling political disagreements and differences in power, worldview, and approaches to the work. They must maintain transparency and engagement in decisionmaking processes while rapidly responding to changing conditions. And they must do all this with an eye to long-term movement impact that transforms relationships of power.

How can movement networks seize the possibilities—and elude the pitfalls—of cross-issue collaboration? Here at the Management Assistance Group, which provides consulting services to nonprofit social-change agents, the question has loomed large in our daily work. To shed some light on the answer, we launched a multipronged inquiry in 2009.

An initial set of interviews with activists and funders helped us to define and describe movement networks; those findings were captured by MAG managing director Robin Katcher in “Unstill Waters: The Fluid Role of Networks in Social Movements,” which appeared in these pages in 2010.2

Next, we explored the qualities that distinguish successful leaders of movement networks. We identified three highly effective leaders: Eveline Shen, of Forward Together; Gustavo Torres, of CASA de Maryland; and Sarita Gupta, of Jobs with Justice. (Gupta also helped organize the Caring Across Generations campaign, which achieved the regulatory victory described above.) Through more than thirty interviews with the leaders and their colleagues, we developed detailed portraits of these three movement network leaders.

Finally, we launched the Network Leadership Innovation Lab, a multiyear program of dialogue, analysis, and active learning. The Lab convenes social change leaders and taps the best thinkers and practitioners to advance our shared knowledge at the intersection of leadership development, organization and network strengthening, and movement building. At Lab convenings, movement network leaders wrestle together with the greatest challenges and rewards of their work.

What We Are Learning

Initially, we hoped to offer some best practices for people and organizations in movement networks—if not “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective Network Leaders,” then at least some widely shared approaches. And we thought that perhaps we could offer some insight into the structures and practices that enable networks to resolve common problems. What we found was less formulaic but a lot more interesting. We learned that:

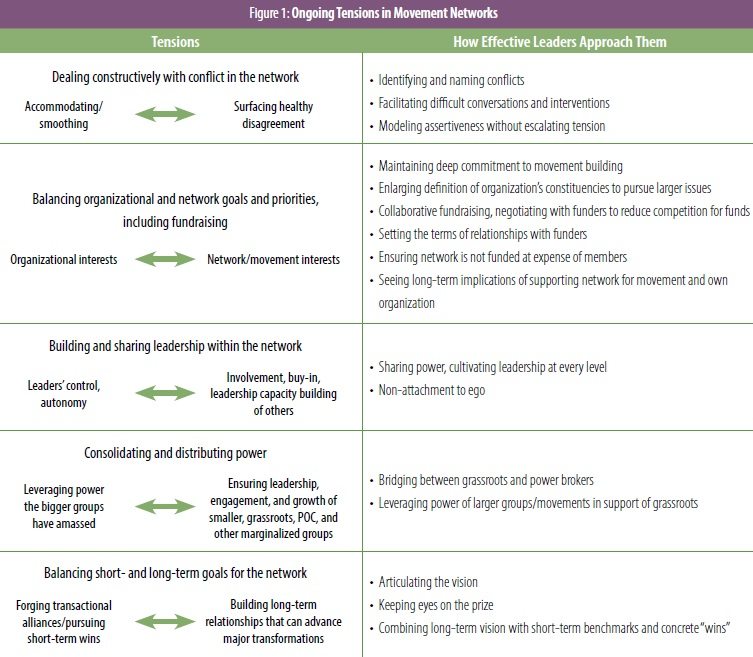

It’s not all about problem solving. As we will explain, movement networks confront a range of unique tensions and challenges (see figure 1). But these tensions are rarely resolved; instead, coping with and balancing seemingly intractable tension becomes second nature for leaders and staff in movement networks.

It’s not all about the leaders. Our focus on leaders changed over time, as we realized that leadership is broadly shared in movement networks (and in the organizations that constitute the networks). Networks and their constituent organizations develop practices and cultures that go far beyond the capacities of a few exceptionally talented leaders. At some point, managing complexity and tensions becomes everyone’s job. This is not to say that leaders are unimportant; rather, network leadership looks very different from traditional models of “heroic” leadership—for example, it doesn’t necessarily come from the top.

It’s not all about the structure. Focus on structure is a red herring in movement networks, whose structures change and adapt with startling frequency. In fact, highly stable structures appear to be impediments to network growth and to the intersectoral alliances at the heart of building movement power.

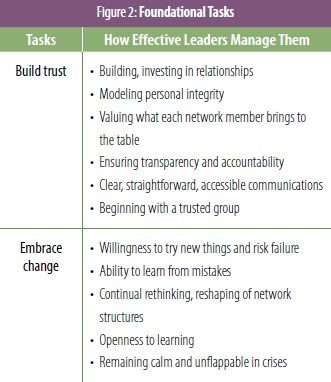

So, what is it all about? From our inquiry so far, we can draw a few preliminary generalizations. First, effective movement networks create a shared culture and mindset among their members, and leaders play an important role in modeling that mindset. Second, while each network culture is unique, all of the effective networks we have studied do two things very well: build trust and embrace change (see figure 2). As we will see, a bedrock foundation of trust and an openness to change can help movement networks navigate (if not resolve) the many challenges inherent in movement building.

In this article, we will share some of the insights gleaned from our inquiry into movement networks. We will delineate the tensions and challenges that networks confront, and offer some observations on how effective network leaders cope with them. We will also show how those leaders foster a culture and mindset that is conducive to success.

But first, a caveat: we recognize that it is far too early in the field’s understanding of movement networks to start proclaiming “best practices” or drawing final conclusions. Indeed, the mind-boggling complexity and dynamism within which these networks and organizations function may mean that we are always evolving useful and promising practices without definitively settling anywhere. Accordingly, we seek to share what we learn as we go along; invite others into the conversation; and hold what we think we’re learning very lightly.

This approach may be unsettling for capacity builders to whom leaders and organizations look for answers. Indeed it has been unsettling for us at MAG. But we shouldn’t be surprised that capacity builders—like the social change agents with whom we work—must learn to adapt to uncertainty and constant change.

A Growing Body of Thought

Our observations about networks harmonize with a growing body of thought about complex systems. For example, Margaret J. Wheatley’s early work with chaos theory challenged the traditional view that organizations behave in predictable, machinelike ways. Instead, Wheatley called for recognition that organizations are living, dynamic organisms in constant flux.3

From the natural sciences comes an understanding of complex adaptive systems (CAS).4 This model, which describes the life cycles of intertwined natural and social systems, has been used to analyze everything from forests to financial markets. CAS thinkers offer insights on building resilience into complex systems; their motto is “embrace change.” In the organizational development realm, Dave Snowden and Mary Boone’s work draws on CAS, as well as cognitive science, psychology, and anthropology, to help organizations navigate complexity and change.5

Our findings also resonate with a body of work on complexity of mind, which sheds light on how adults evolve their ability to process abstraction, and Jennifer Garvey Berger’s use of that theory to develop more agile leadership for changing times.6 Ronald Heifetz’s work on adaptive leadership in novel and challenging situations applies as well.7

And there is overlap between our findings and new thinking on nonprofit networks and leadership, notably a pair of recent reports published by Grantmakers for Effective Organizations (GEO).8 The GEO reports observe that effective networks require a distinctive mindset and “a stance toward leadership that prioritizes openness, transparency, making connections, and sharing control.”9 Similarly, research by the Building Movement Project concluded that successful shared leadership depends more on foundational work and practices than on any particular structure.10

Finally, it’s worth noting that much of the new thinking about coping with complexity bears a striking resemblance to some very old thinking. For example, Zen Buddhism emphasizes impermanence and the interconnectedness of all things—an apt description of the movement network context. Other tenets of ancient traditions—letting go, nonattachment to ego, and compassion—frequently appear explicitly or implicitly in our case interviews as useful approaches for navigating the unstill waters of movement networks.

Challenges for Leaders in Movement Networks

In addition to the challenges that confront all nonprofit organizations, movement networks face certain inherent tensions and polarities. Network leaders play an important role in modeling a response to those tensions. Critically, successful leaders help their networks achieve two foundational tasks:

Building trust. This is the most fundamental, irreducible task for movement network leaders and members. Trust is the glue that holds networks together, binding leaders, organizations, constituency groups, issues, and sectors. Not surprisingly, each of the network leaders we have studied has an extraordinary ability to cultivate trust among colleagues and allies.

“She inherently builds a bedrock level of trust,” says a colleague of Gupta’s, executive director of Jobs with Justice. Gupta builds trust through longterm reciprocal relationships: “Fair exchange is not a hobby for her,” adds the colleague. “It’s very genuine and not just about getting what she needs. It’s about her being in relationship with others. She reciprocates; she’ll be there for you.”11

Some movement networks develop trust over time; others grow from a base of solid relationships. Eveline Shen and her allies at Forward Together followed the latter trajectory. “I had been part of many coalitions that had fallen apart,” Shen explains. “I wanted to figure out how to build something that would have strong enough glue that could utilize the inevitable disagreements that people are going to have when they work together [to build] collective understanding and strength.”

In any case, maintaining a solid base of trusting relationships can pose significant challenges as a network grows. For network leaders, there is a painful irony: the more successful they are at building relationships and connecting with others, the greater the number of relationships they will have to manage, and the less time they will have for each.

Embracing change. Movement networks and the issues they address are ever changing, so a capacity to thrive in the face of change and uncertainty is key. As one member of the Jobs with Justice network explains, “Comfort with uncertainty means accepting all the discomfort of it and acknowledging that it’s real, and then just being with the response to it. So that’s part of it—really figuring out how you can shape an organizational culture around that.”

Movement-oriented organizations can grow and change with head-spinning rapidity. At Forward Together, one staffer observed, “This is a staff that has doubled and more in size in the last two years. This is a staff for which most people’s job descriptions have changed at least once in the last two years. This is an organization that five years ago was locally focused, then had a reproductive justice network, and now has changed its name and is a multiracial, national movement-building organization.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Successful movement networks have many ways of coping with change, but one common thread is a willingness to try new things, risk failure, and learn from one’s mistakes. As a colleague said of Shen, “She is not afraid of being wrong. . . . She is not afraid of telling people, ‘This is what we tried and it didn’t work, so let’s try something else.’”

Networks that have achieved these foundational tasks are well positioned to deal with the following five ongoing tensions in movement network building:

Dealing constructively with conflict in the network. This is akin to dealing with conflict within a single organization, but on a vastly different scale. Movement networks are inherently conflict laden, and their members are bound more loosely than co-workers within an organization. No one has the formal authority to hire, fire, or enforce compliance using the power of his or her position. To prevent conflicts from spinning out of control, network leaders must find the right balance between accommodating differences or smoothing over tensions on the one hand, and surfacing healthy disagreements on the other.

Successful network leaders are able to address important issues without escalating tensions. As a colleague said of Torres, “[He] is able to voice his positions and his opinion in a way that doesn’t needlessly antagonize those who disagree with him.” Gustavo has demonstrated an ability to constructively address even the most inflammatory tensions around race and class. As another colleague observes, “He won’t say, ‘Why do you, white person, feel like you should be dominating this discussion on immigrant rights?’ But he’ll say, ‘Wow, I’m really shocked that I’m the only Latino sitting at this table in the campaign for immigrant rights.’”

In EMERJ, one of the networks Shen helped to create, dealing with conflict was woven into the culture from the start. “From the minute we walked in the door to our first EMERJ convening,” says one participant, “there was (a) an assumption that everyone had an organizational agenda; (b) no judgment about that agenda; (c) an expectation that there would be conflict; and, therefore, (d) we had to have something in place to handle conflict so that we could move on, so that we didn’t set ourselves up for a situation where if we disagreed about something deeply, people would leave EMERJ.” Another participant recalls, “I literally learned a new approach—that you could address conflict head on without damaging the person, the organization, or the entity that you disagree with.”

Balancing organizational and network goals and priorities. Network leaders must protect and advance the interests of their own organizations, as well as those of the network as a whole. In some networks, this tension is negligible, because the interests of the network and its component groups are so closely aligned. More typically, tensions surface over issues such as visibility, credit for achievements, nuances in political positions, willingness to utilize different strategies and tactics, and the needs and concerns of various constituencies.

Perhaps the most corrosive tensions arise over the ever-present issue of money. Successful movement networks neutralize this tension by finding ways to reduce competition for funds. Some engage in collaborative fundraising, consolidating many groups into a single “bargaining unit” that funders can’t ignore. Others take pains to ensure that the network is not funded at the expense of its members. For example, when Jobs with Justice and other groups launched the UNITY alliance, they made it clear to funders that money for UNITY should come from larger foundations with more resources, rather than from smaller foundations that provided essential funding to UNITY’s component groups.

Building and sharing leadership within the network. No one person leads a network; by definition, leadership in movement networks is widely distributed. The networks we studied have countless leaders working at all levels—from neighborhood block captains to the CEOs of national organizations. Successful network leaders must constantly weigh their own control and autonomy against the larger goal of building leadership in the network. The leaders we profiled are often willing to sacrifice the former for the latter, and they are all exceptionally adept at cultivating the leadership of others.

A colleague of Torres’s recalls, “When I was beginning to work with him, I was a little bit afraid of public speaking, and he threw me in front of two thousand members. I was like, ‘You really are insane. You want me to speak? I have not rehearsed a speech.’ He was like, ‘You have it in you. It’s in your heart.’ Then he threw me the microphone, and therefore I had no choice. What did I do? I spoke, and I spoke from my heart. That’s when I discovered that I could do this. I would not have found out if Gustavo didn’t throw me that microphone.”

Consolidating and distributing power. A similar dynamic plays out on a larger scale, as network leaders weigh the benefits of consolidating the influence of larger organizations against the need to empower smaller grassroots and marginalized groups. The most effective movement networks manage to do both, by remaining accountable to their grassroots base and connecting that base to the levers of power.

Jobs with Justice, for example, has helped create networks that include the nation’s largest labor unions, as well as some of the most marginalized, non-union workers. Two of those networks—the Excluded Workers Congress and the Caring Across Generations campaign—leveraged the influence of the labor movement to win the new protections for home caregivers described above.

And CASA de Maryland combines services and advocacy in a way that builds the political power of its base. Providing direct services—such as job training and legal assistance—gives CASA a profound, real-time understanding of the issues affecting its constituents, which in turn shapes its advocacy and policy work. “When there are policy discussions,” says Torres, “we can bring the perspective and the experiences that happened two days ago, as opposed to something that’s in a report.” CASA also connects the people it serves to broader struggles for social justice. As one CASA staffer puts it, “As soon as we hear a story from an individual, we help them see the big picture. It’s our job to say, ‘Unfortunately, there are thousands of people in your situation.’ It’s at that level, really, where an individual goes from ‘I have a problem’ to ‘we have a problem.’”

Balancing short- and long-term goals for the network. Most organizations work to balance short- and long-term goals, but the task is exponentially more difficult in networks, which require buy-in from a much larger and more diverse set of actors. Moreover, this balancing act can determine whether a movement network emerges at all, as leaders choose whether to forge temporary, transactional coalitions conducive to short-term wins, or to invest in long-term relationships that can also advance major transformations. Successful network leaders are adept at integrating short- and long-term goals. They articulate and embrace an inspiring long-term vision while pursuing achievable wins that keep network members motivated.

The leaders we profiled are all described as visionaries by their peers. As one colleague said of Shen, “I can count on one hand the number of true thought leaders in this movement, and if I’m starting with my thumb, she’s the thumb.” Of Gupta, a colleague observed, “She provides the visionary glue” that holds the network together. That quality can see a network through many difficult times. Speaking of Torres, a colleague said, “I feel like he always calls us to the higher purpose. It’s very easy in networks to get into process tangles and organizational turf issues, and I think he is always guided by the North Star of freedom for our people. I feel like it unsticks us time and time again, that crystal clarity. Everything else seems like a small issue when he brings us back there.”

Second Nature: Creating Culture in Movement Networks

In effective networks, mastering foundational tasks and coping with tensions becomes second nature for everyone—not just leaders. Still, leaders play an important role in shaping the network’s culture by:

Modeling effective attitudes and practices. While traditional models of heroic leadership are not useful in highly networked settings, the attitudes and practices of leaders can set a powerful example. For example, if leaders want to cultivate trust, they must be trustworthy. If they want to build the leadership of others, they must be willing to hand over the reins (or the microphone). And if they want the network to be agile and adaptable, they must be willing to take risks and learn from mistakes.

Setting up flexible structures. Successful movement network leaders do not become unduly attached to specific structures. In fact, many hail from a new generation that is questioning and continually remaking organizational structures in the service of the movement rather than in the service of building enduring organizational forms. Often, these leaders find that it is more helpful to institutionalize processes rather than structures.

Getting the right staff and growing their leadership. Effective movement network leaders make a point of hiring and retaining staff who are open to change in their roles and responsibilities and comfortable dealing with ambiguity and complexity. As Shen describes her approach, “I think what it takes to do this work successfully is that you contribute what you can, but you create ongoing opportunities for people to lead, and you do what you can to lift all boats—to shine the light on as many leaders as possible, as many people as possible.”

Creating opportunities for self- and collective reflection. In order to observe and adapt to changes in the network and its environment, effective leaders create space for reflection—such as sabbaticals, retreats, and regular staff meetings.

Being relentlessly explicit about values, principles, and practices. Movement networks are not built; they are lived. The work of establishing the network’s culture is ongoing. Effective network leaders continually create—and revise—formal and informal systems to reinforce the network culture. Reinforcing network culture from within their own organizations can mean ensuring accountability—for example, by moving staff out of the organization if they are unable to meet the demands of a networked environment. Reinforcing the culture of the movement network itself can mean skillfully but explicitly pointing out when oneself or another network member is not living up to agreed principles and values.

Encouraging self-care. Working for social change is rewarding but difficult. Successful network leaders make it look easy, but their equilibrium often rests on a foundation of internal work, discipline, and self-care. By modeling those behaviors for staff and colleagues, and enabling others to care for themselves, movement network leaders can prevent burnout and help their colleagues stay in it for the long haul.

Challenges, and Areas of Future Focus

To date, our inquiry has given us considerable insight into culture and leadership in effective movement networks. But many questions remain. In our work with clients, and in convenings of the Network Leadership Innovation Lab, we have identified several topics for future exploration:

Structural funding constraints. Even the most effective movement networks struggle with funding norms and requirements that are not yet attuned to these new ways of working. This is by far the most frequently mentioned challenge for movement-oriented organizations and networks.

MAG is working to jumpstart new thinking about network funding in two ways. First, participants in our Network Leadership Innovation Lab have launched an action-learning project on the financial independence and sustainability of social justice organizations, which is exploring how social justice organizations can resource themselves in a way that allows them to more effectively and independently pursue their missions.

MAG is working to jumpstart new thinking about network funding in two ways. First, participants in our Network Leadership Innovation Lab have launched an action-learning project on the financial independence and sustainability of social justice organizations, which is exploring how social justice organizations can resource themselves in a way that allows them to more effectively and independently pursue their missions.

Second, the Lab has been hosting and participating in dialogues with grantmakers interested in supporting movements and networks. These include two MAG-facilitated gatherings—one in October 2011 and another in September 2012—that drew more than forty funders as well as presentations at the Grantmakers for Effective Organizations “Supporting Movements” conference in November 2013. Through these dialogues, we are developing resources and exploring complex adaptive philanthropy.”

Sustaining one’s self in the work. While the importance of self-care is widely acknowledged, this remains an aspirational goal for many of the network leaders we know. Topics for future exploration include knowing when to ask for help and building reflection and self-care into organizational culture.

Endings. Movement networks move through phases and life cycles; alliances are formed and dissolved. Yet many network leaders find it difficult to end long-term alliances in ways that do not damage their organization or key relationships.

Strange bedfellows. Engaging with unlikely allies can be enormously productive, but trust and communication across cultural and ideological boundaries can pose significant challenges.

Catalyzing learning. “Embracing change” means openness to new ways of thinking, understanding, and doing the work. The challenge is to embed mutual

learning into the culture and mindset of movement networks.

In the coming months, MAG will engage these topics through the Network Leadership Innova-tion Lab, and with a much larger group of conversants through our online platform. We invite you to join the conversation at network leadership.org and on Facebook at facebook.com/ManagementAssistanceGroup, and follow us on Twitter @mgmtassistance.

• • •

When members of the Caring Across Generations campaign stood beside President Obama as he approved sweeping new protections for home caregivers, they demonstrated the power and the promise of movement networks. To realize that promise, we must embrace new models of leadership, build organizations that think and work differently, and create spaces for leaders to innovate and evolve. The challenges are great, but the rewards are greater still. By transcending organizational and issue boundaries, movement networks can build the power we need to make deep and lasting social change.

Notes

- Robin Katcher, “Unstill Waters: The Fluid Role of Networks in Social Movements,” The Nonprofit Quarterly 17, no. 2 (summer 2010): 52–61, dev-npq-site.pantheonsite.io/policysocial-context/5511-unstill-waters-the-fluid-role-of-networks-in-social-movements.html, and reprinted in The Nonprofit Quarterly 19, no. 4 (winter 2012): 58–63; The Network Innovation Leadership Lab, Movement Network Leader Case Study: Sarita Gupta; Movement Network Leader Case Study: Eveline Shen; and Movement Network Leader Case Study: Gustavo Torres (Washington, DC: Management Assistance Group, 2012 and 2013), networkleadership.org/lab-publications/.

- Ibid.

- Margaret J. Wheatley, Leadership and the New Science: Discovering Order in a Chaotic World, 3rd ed. (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2006).

- Lance H. Gunderson and C. S. Holling, eds., Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Washington DC: Island Press, 2002).

- David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making,” Harvard Business Review 85, no. 11 (November 2007): 68–76, hbr.org/product/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making/an/R0711C-PDF-ENG.

- Robert Kegan, In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994); Jennifer Garvey Berger, Changing on the Job: Developing Leaders for a Complex World (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011).

- Ronald Heifetz, Alexander Grashow, and Marty Linsky, The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2009).

- Jane Wei-Skillern, Nora Silver, and Eric Heitz, Cracking the Network Code: Four Principles for Grantmakers (Washington, DC: Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, 2013), geofunders.org /geo-publications/680-network-code; Grantmakers for Effective Organizations and Monitor Institute, Catalyzing Networks for Social Change: A Funder’s Guide (Washington, DC: Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, 2011), geofunders.org/geo-publications/566-networks.

- Grantmakers for Effective Organizations and Monitor Institute, Catalyzing Networks for Social Change, 3.

- Caroline McAndrews, Frances Kunreuther, and Shifra Bronznick, Structuring Leadership: Alternative Models for Distributing Power and Decision-making in Nonprofit Organizations (New York: Building Movement Project, 2011), buildingmovement.org/pdf/bmp_structuringleadership_1.pdf.

- This and all following quotes are from interviews conducted by the authors.